Fourth Sunday in Advent | Luke 1:39-55

Lectionary Project—Third year of weekly posts based on the Gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary

A baby kicks in the womb. That’s all that is happening in this story, really, just an ordinary thing. But it is the kind of small ordinary event to which we attribute meaning, a sign, or some superstitious belief from old wives’ tales. A broom falls. A palm itches. A child kicks in the womb.

That’s all it is.

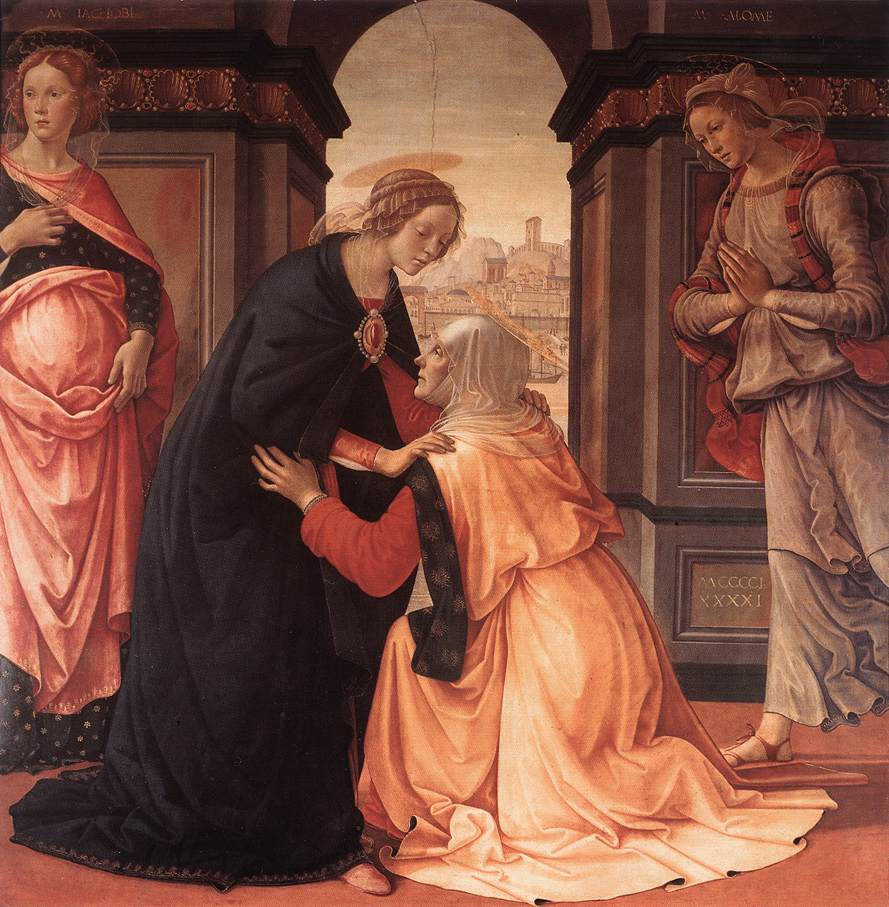

In that simple kick, two women know portents of the future. They hear angels greeting them. They believe that the first Christmas is coming, before there is such a thing as Christmas. And they give praise to a God whom they have never seen, comfort one another in their faith that all will be well, simply because of a child’s restless dream in the warm darkness of his mother’s womb.

Two expectant mothers, one of them old, one of them young and as yet unwed, sit at the beginning of a new creation story. God is bringing about a new thing, and it starts in these two women who are not seen by anyone in their world as persons of greatness or importance.

There is a powerful dichotomy at work. The low are raised, and the rich and powerful are rejected. God’s value system is different than ours.

“My soul magnifies the Lord…” So begins the famous praise offered by Mary in Luke’s Gospel. The tension is plain in the text. Far from being a simple expression of faith, Mary’s words distill the message of the prophets. Her prophetic word to her world, and to ours, is that the proud shall be scattered, those who rule shall be torn from their thrones, and the rich shall go hungry. It is the gospel told as prophecy and as challenge—God shall favor the humble, empower the weak, feed the hungry. True power is not in governments or bank vaults or armies, the prophets are saying. True power, Mary tells us, is in the ability to create life, not destroy it. And we can see the face of God in every newborn child.

People speak of Mary’s humility, her willingness to submit to what she perceived as the will of God, and they are right to do so. We should also list her among the prophets, like Elijah and Isaiah. In her grace and her humility, Mary gave us words of power and of warning.

In this Advent season, we would do well to look for the dichotomy of the prophets, this tension Mary proclaims at the coming of the first Christmas. If we think ourselves clever, or powerful, or rich and well fed, then Mary is warning us.

Theotokos, they called her, God-bearer, but that was many years afterward, when enough time and enough words had passed to help the early Church see what had happened. When the Christ child was born and God in that moment began the making of a new creation, Mary was still in a stable, with straw for her bed, animals for her companions. In Bethlehem, she was a stranger who had travelled from far away. She was of low estate, no one of power, no one of wealth. And most blessed was she among us all.