Luke 18:9-14 | Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost

He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt…

Well, that really says it all, doesn’t it? Except we still have the notion that the words are aimed at other people. Like Trump supporters. Or Hillary people. Or even Bernie folk.

There’s nothing quite as satisfying as being right, unless it is the certainty that other people are wrong. That’s particularly true when we think we have God on our side.

Except that God doesn’t take sides. Not yours, not mine. Not the side of those people over there.

That seems to be the point of the gospel message, that God takes no one’s side, or maybe takes everyone’s side, but most of all that God invites us, expects us, to take God’s side. Not that we are to be right. Not that we tell others that they are wrong.

The point of the gospel is that we are all instruments of grace, which isn’t ours to keep or give away.

When we see people hungry, we are supposed to feed them.

When we see people without a home or clothes, we are supposed to find homes for them. We’re supposed to clothe them.

When we see people ignorant and without skills or opportunity, we are supposed to teach them and prop open the door.

When we see them sick, we’re to bring them balm. And doctors. And clean water and mosquito nets. We’re supposed to make sure their children don’t die of a disease we’re not even exposed to anymore. We’re supposed to make sure their children don’t get shot trying to walk to school.

When we forgive others, we’re supposed to do it the way we’d like to be forgiven.

Hey, that’s pure gospel. Blame Jesus. And no, we don’t get an escape clause if the hungry people are part of a different religion, or have a different skin color, or don’t conjugate their verbs well because of poor education, or don’t speak English at all.

The only thing the overwhelming majority of needy people ever did was to get themselves born in the wrong place. Let’s think about that. When we see needy people, we might consider what brave and brilliant and wondrous things we did to be born to a better life.

Yes, work is important. And responsibility. And making something of yourself. And ‘God helps those who help themselves’ must be written somewhere, just nowhere in scripture.

So is grace important. And opportunity. And human decency, let alone Christian compassion.

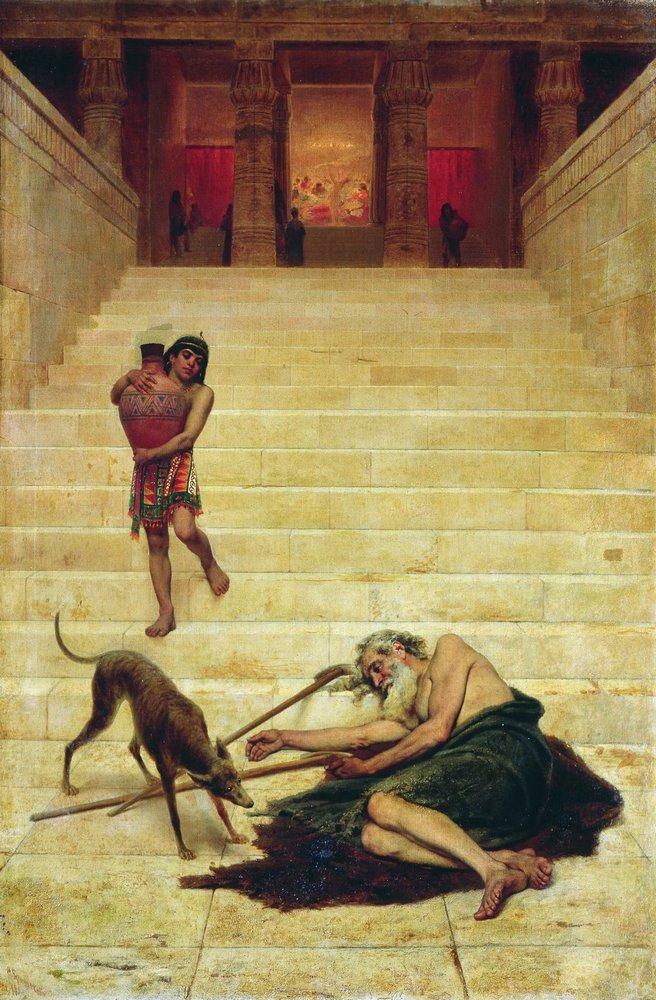

“I thank you God that I am not like other people,” said one fellow, the one Jesus held up to ridicule.

Admit it. We think the same way as that fellow. On some level, when we see the homeless or the poor or the dispossessed, we think something like the same thought, and we think we are being grateful. We think we are being faithful and humble. The last thing we think is that we are precisely the people Jesus was talking to.

I’m afraid that this is genuine gospel stuff. It’s not the popular kind, but it is the kind Jesus taught. It’s the kind of thing that made people want to crucify him. If we Christians don’t like it, maybe we should try a different religion.

If we’re tired of just being right, and want to do right, there are plenty of opportunities, probably starting in our own homes and neighborhoods. Faith isn’t what we say. It’s what we do.

Here’s a great place to start: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/

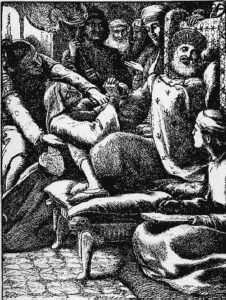

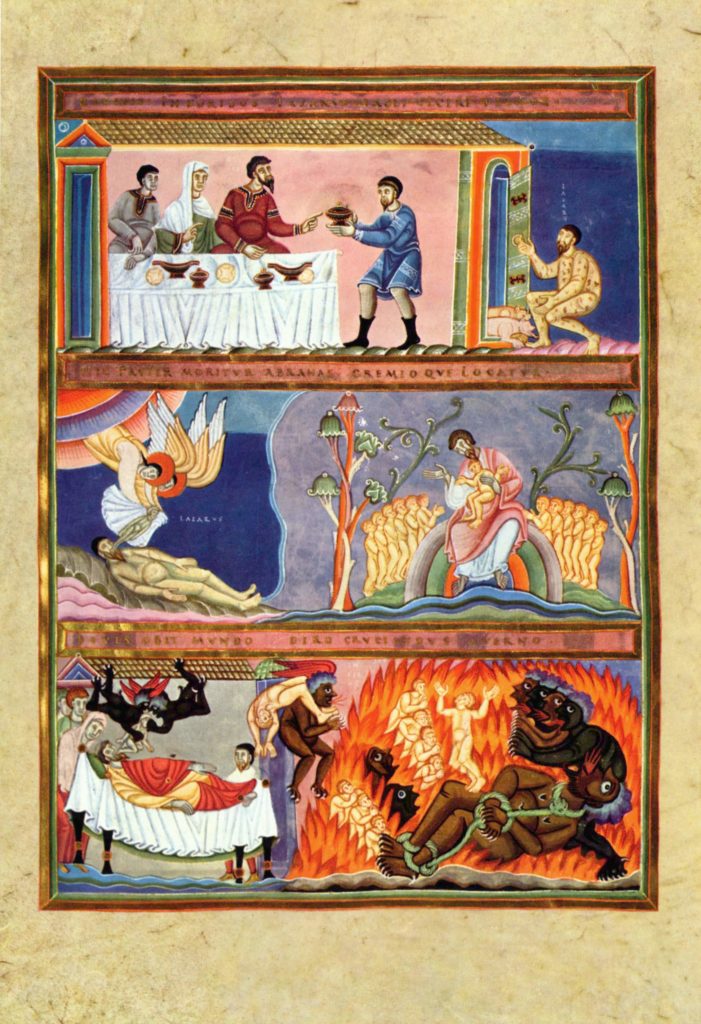

![Hendrick ter Brugghen [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://crtaylorbooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Hendrick_ter_Brugghen_-_The_Rich_Man_and_the_Poor_Lazarus_-_Google_Art_Project-300x241.jpg)